These are some Rosies in many states

THE TODAY SHOW: THANKING ROSIES

On Christmas Eve of 2012, the Today Show aired a piece for Rosies with our help. This beautiful segment is set in an original factory where real Rosies worked at during WWII as a celebration of their efforts.

Rosies at Work to Preserve their Legacy

Over the years, we at American Rosie Movement™ have diligently tried to find, interview, and work with Rosies, often with many kinds of partners. By listening to some of these interviews on Dropbox, you will find Rosies' stories fascinating, inspiring, and deeply human.

As you listen, keep in mind that Rosies have lived for almost a century. They give us a view of the fuller story of war, caring for wounded veterans, raising children who believe in women's potential, and how greatly seniors can contribute to any healthy society.

Remember that Rosies not only worked in factories, but their home front work also included jobs for shipyards, governments, farms, and more. Today, our national conscience and promises require that you help them pass their legacy of quality work and unity to the future.

Stay tuned, we have more interviews coming!

MEET ROSIES FROM ACROSS THE NATION

American Rosie Movement™ and the Rosie the Riveter Trust met with various Rosies on December 14, 2020. American Rosie Movement™ and different partners plan similar meetings in the future, so let us know if you want to meet Rosies through Zoom and Teleconferences.

ROSIE PROFILES

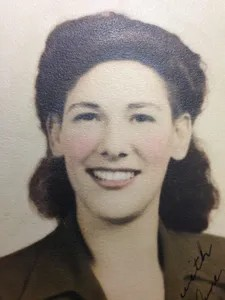

Ruth Edwards

Ruth was an “expeditor” at Carnegie Steel at the Naval Ordnance Center in Charleston, West Virginia. This meant she went from one workstation to another to learn what they needed. The plant made metal items, such as Tiny Tim Rockets and was so large that it housed several plants within the plant.

Through the war, her sweetheart, Jimmy Edwards, was in the Pacific, including at the Bataan March. He never fully recovered physically or emotionally from this dark experience. Jimmy died some years ago, and Ruth has lost one of two sons.

As the primary “bread-winner” Ruth advanced from secretary to Director of all Business Education for the State of West Virginia.

Ruth has helped with the American Rosie Movement™ from its beginning, starting with being one of 31 Rosies in the documentary film called, We Pull Together: Rosie the Riveters Then and Now. Today, Ruth has helped plan: a) the first park created by Rosies, b) events, such as when Belgium and UK thanked American Roses, and c) the Today Show which was taped at the plant where she worked.

She is a board of directors member for Thanks! Plain and Simple™, after serving on boards for many for-profit and non-profit organizations. She now lives in Greensboro, SC, where she was recently interviewed for the biography of Charles Yeager, who was her classmate in public schools.

June Robbins

June started life in 1926 in poverty during the Great Depression, and she often had to move in with various relatives. She did well in school, was editor of her high school paper, and met her husband-to-be, Melvin Robbins, when she was 15 and he was 17. She convinced a drafting teacher to accept her as the first and only girl in class, so that she could go to work in the Philadelphia Navy Yard where her mother worked on ship barriers, parachutes, and in the War Room.

Many boys in June’s high school volunteered for the military, which is what Melvin did, instead of waiting to be drafted. Everyone knew someone who had been killed or wounded. Melvin came back, and they had a full and rewarding life together.

“I was thrilled to work at the Navy Yard at 17 to help the war effort and to help my mother, who was then single. I helped to draft paravanes, which were strung out along the sides of the ship, to prevent mines from destroying the ship. One day after working a long time designing them, I got to see one. I still have some of my drafting equipment.”

June worked mostly with men, who treated her respectfully, though they sometimes clowned around and teased her. She recalled the officers playing the war game where they moved model ships about on a large board to test their tactical skills, eating lunch with the sailors and officers, and the stress on getting back to work and doing it well, no matter what was going on in the yard.

June and her mother listened to a radio station that played Bluebird of Happiness every hour, and they knew it was time to leave for work when it played that song in the mornings. Along with working, June volunteered with the Red Cross and became a hostess at the USO.

She and Mel married in 1947. She worked as a hairdresser, helped Mel start his business as a store owner, became a mother of seven children, and joined B’nai Brith Women, to fulfill the Jewish ideal of “Tikun Olam,” to “Repair the World.” June lived in Israel with her family for a year and eventually volunteered there on an archeological dig of Roman artifacts in Beit Shean. Her sons taught her to ride a motorcycle, which was her transportation for several years.

She was a “humorologist” at Children’s Hospital for many years.

Eventually, she became a professional clown after extended training, and she now goes to veterans’ hospitals, women’s shelters, and other places, “to lighten their lives.” She won first place for her “Hungry Hobo” skit at the 2013 Mid-Atlantic Clown Association (MACA) convention in Pennsylvania. She says the key to improvising is to listen.

Months after being named in the press as “The Cutest Couple in Marple-Newtown,” having been married over 65 years, June lost her beloved Melvin in August 2013. Their seven children, 18 grandchildren, and 8 great-grandchildren are devoted, and many are nearby.

As a social worker with clients over the age of 60, and an Area Agency on Aging, her daughter, Gloria Joffe proudly says that she knows an 88-year-old, professional clown, who found the many things she has tried and has accomplished in her life.

If asked what she is proudest of in her life, June will say her family, but she is also proud of her clowning, getting people to laugh, and, of course, what she and other women accomplished in the war effort. She always has a sense of the importance of pulling together, just as Rosie the Riveter was known for.

Rose Shelengian

Rose (Vartouhi) was born in Bridgewater, Massachusetts to Haroutune and Armenouhi (Der Avedisian) Basmajian, who had arrived the year prior from Constantinople with her sister Madeline. Her mother was a survivor of the Armenian genocide and her father was a freedom fighter who had returned to Turkey from America in 1915 to fight in General Antranik’s army and protect his homeland. Rose and her sister grew up in Bridgewater’s small community of Armenians, where they attended Saturday Armenian school and had adventures with the town's other Armenian children. They also experienced discrimination as their classmates referred to them as “foreigners”. Bridgewater’s factories closed during the Great Depression and so in 1935 the family moved to Philadelphia where they had relatives. It was quite an adjustment for Rose to adapt to city life after growing up in a rural town, but over the years she joined the Armenian Youth Federation, in which she later served as treasurer, got to know fellow young Armenians, and performed in plays put on at her church. Rose’s dream was to go to college and become a teacher, however her mother’s premature death when Rose was 13 in 1938 set her and her sister on a course to support their father at home instead.

Rose graduated from West Philadelphia High School in 1942 and the following year with the men away at war she took a job at a defense plant in Westinghouse’s turbine division in Essington near the city. Her main job was working on a surface grinder to cut stock down to the required dimensions. The work was top secret and the women in the plant, now famously known by the moniker “Rosie the Riveter”, didn’t even know precisely what their work was used for. Even though she had no prior experience, Rose quickly learned how to use these dangerous technical tools, how to read blueprints, and even wore pants for the first time as they were strictly men’s clothing. She was even the only woman in the plant asked to work a huge machine called a lathe reserved for men. She described her time in the plant by saying “it was a lot of heavy work, lots of noise and dust, so we were exposed to a great deal, but I felt that it was the least we could do – especially considering what the boys were going through on the battlefield.” She didn’t know any other Armenian girls who did such a job and didn’t tell others about what she did since a woman working in that way was so unusual in the community.

After the war, the boys returned from service and she began seeing one of them, Martin Shelengian. They married on November 1, 1947 and had three children. They moved to Broomall in 1958 where they were joined by many other Armenians over the years. Perhaps encouraged by her previous experiences in the workforce, after Marty temporarily lost his job with General Electric in 1960, Rose went out and found a job, and continued to work as a secretary for the next 35 years. She only retired at age 70 because she figured it was time, but felt she could have continued on for many more years. This is not surprising from a woman who couldn’t be stopped from shoveling her driveway into her mid-80s. Her biggest role in later life was that of grandmother of 5 and a support to Marty until his death in 2011. Recently Rose became a great-grandmother as well, one of which was named for her. Fiercely independent, Rose took care of the house and remained at home until turning 95.

A beautiful closing act for her has been the re-appreciation of her service as a “Rosie”. While she had never thought she had done anything extraordinary, the importance of these women has come to be recognized in recent years. She became involved in the Rosie the Riveter Movement, spreading awareness about its spirit of unity and working together, something much needed today. A special memory for her was being honored as a Rosie by the Mayor of Philadelphia at the Liberty Bell in 2017. She also was featured in a radio podcast last year telling the story of her service.

Rose passed away in December of 2020. Her obituary can be found here: https://www.inquirer.com/obituaries/rose-shelengian-obit-obituary-20210113.html

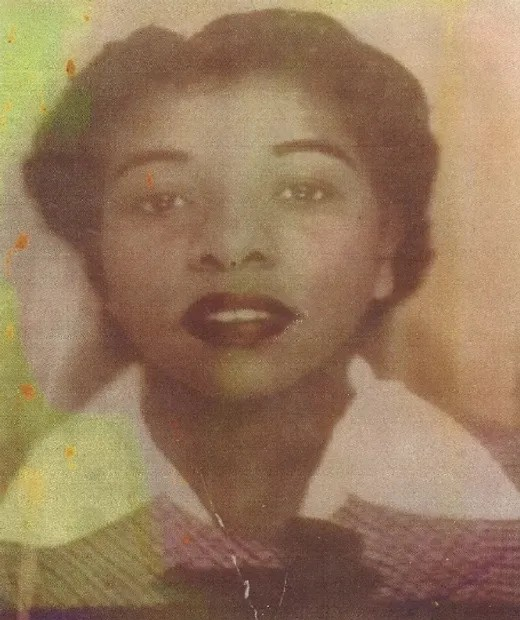

Gladys Reese

Gladys Reese’s story is not only about the pioneering work of Rosies; it is a story of integration in America. She grew up in Fayette County, West Virginia on land her family owned. Both her parents died when she was a small child.

She had to ride a school bus about 60 miles one way, and pass many white schools because of segregation. As she graduated from high school, a teacher took her to Detroit where she became a metal worker.

The workplace was integrated, but when she went to restaurants, she had to wait at the back door for her food. Soon, Gladys and her friends realized they could take a short bus trip to Canada where they were welcome to shop and eat in public places.

After the war, she and her husband had both their own and foster children who have been very supportive of her telling her story. One foster child, Charles Pryce, has written poetry about the Rosies that he has read at various events.

Several organizations, such as the Lion's Club, have helped Gladys make her story known in her community. Now, we hope that you can help us find more African-American Rosies and highlight how they are part of America's past, present, and future.

Gladys Reese and Agnes Smith

Gladys Reese (left) grew up in Fayette County, WV, and had to travel 70 miles to a school that accepted African Americans. She worked in Detroit, Michigan, as a metalworker. After her shift was over, she could not go into restaurants and had to wait for her food at the back door. She and other African American Rosies learned that they could take a bus and in half an hour be in Canada, where they could be served with no problem. Gladys helped to integrate businesses in Charleston and forgave the Daughters of the American Revolution for rejecting Marian Anderson in the 1930s.

Agnes Smith (right) was the daughter of a Polish couple who came to America before the war, and her father worked in Pennsylvania coal mines. She had two male cousins in Poland who went into the woods with an axe and broke each other's leg so that they would not have to march in Hitler’s Army. During the war, she drove an overhead crane in a factory that coated engine parts to extend the life of engines.

Buddie Curnutte

Buddie Curnutte is outstanding because she is one of an estimated six million women who worked on the home front during World War II, and she has survived with well-functioning mind and body, and she lives a life of caring, and she has shown consistent commitment to helping our nonprofit organization develop model Rosie the Riveter Project.

She grew up poor in Apalachin, New York during the depression. She and her brother were raised by their father who was not around. In adolescence her aunt took her to clean, then her uncle had her watch an empty building which she still worries may have been, something illegal. While working at a five and dime store, friends Fran and Betty, found an ad for defense plant work in Cheektowaga, NY. She says Curtis Wright's riveter training was four weeks unpaid, with no guaranteed job for poor performers.

She describes how women worked in pairs on the Kitty Hawk airplanes, one a riveter and one a bucker, and says she can still drill today. She worked on one part of the wing assembly. “It was hard, and you worried, lives were in your hands.”

After two years of riveting, she joined the coast guard to travel the west and the world. Her unit trained at Sheepshead’s Bay, NY, in hard winter, without uniforms, or proper shoes. She became a medic, and at a Philadelphia hospital, she met Earl Curnutte, who had lost a leg and injured his foot at Okinawa. He was released after the war. They wrote but never heard each other’s voices.

On July 3, 1946, at 11:00 p.m., he climbed three flights of stairs of a Catholic hospital, entered the nurses’ station, and said, “I’ve come to marry Buddie.” They drove nonstop to Charleston, WV, found a minister from the phonebook who, on their arrival, was a mortician who married them at the funeral home.

On July 3, 1946, at 11:00 p.m., he climbed three flights of stairs of a Catholic hospital, entered the nurses’ station, and said, “I’ve come to marry Buddie.” They drove nonstop to Charleston, WV, found a minister from the phonebook who, on their arrival, was a mortician who married them at the funeral home.

In 2010, we interviewed Buddie (see a documentary film). Buddie is an example that Rosies are precious illustrations of largely-ignored women critical to a phenomenal human effort. In 2011, she joined our Board of Directors. Soon after, Nancy Sneed-Sample, another Rosie board member, died, leaving Buddie as the daily link to help us find, interview, include, and educate with (not just about) Rosies. We believe our work is a model for America. We know that Buddie is a model for people.

Dot Foster

“Dotty” Foster was born Dorothy Johnson in Lanchester, England, moved to Cheshire County at 10 years old, and worked in Manchester County during the war, in northwest England. Manchester had a strong industrial history, had the first railway station, hosted the first meeting of the Trades Union Congress, and is where scientists first split the atom and developed the first programmable computer.

She worked at Broadheath, in a factory that had converted from making linotype to munitions when she was 14. She says, “I was glad to sweep the floor for the war effort. I became pretty skilled. I learned to run a drill and a lathe, to do milling and filing.”

Dot’s father fought in WWI, after being orphaned when his father, a coal miner, died of black lung disease and his mother died soon after. Her brother was killed on the Hurricane, a ship that chased German submarines.

She says, “There were no dances or ball games or things kids do today.”

She fell in love with an American. On their wedding day, since there was no nylon hose, she did what many women did, painted her legs with makeup, then took eyebrow pencil and drew a line up the back of her leg to look like the seam in “nylons.”

Her memories of coming to rural America are vivid, and she often talks about the inherent strength of women to see things through. Her first husband died when they had three children. She says, ”By the grace of God, I had wonderful neighbors. In his life, we have to be there for one another. I had no family. You have to make your notch in life, but no one can do it alone. People who haven’t experienced things can’t imagine. It takes tough times to soften you. Particularly women. We can put ourselves in others’ shoes because we have had to endure so much, and often silently.”

Pauline Adkins

Pauline Adkins was born in 1928 in Logan County, West Virginia in the heart of coal-mining country. One of her ancestors is Chief Cornstalk, a historic native American. At 11 months old, a combination of childhood illnesses left her virtually deaf. She started to school three different years before she decided to stay. On her third try, her teacher, Mrs. Edna Frasher, decided she would help Pauline learn. Pauline loved to read from early in school. When she was 15, she worked for the Civil Air Patrol.

At age 18, she began working at Sylvania Corporation, making tubes for rockets on the assembly line. She can tell you in detail about the positions she worked on the line, the holes, the wires, the grids, and how the tray went down the line from position to position. Her pay was far less than a dollar an hour, and her plant in Huntington, West Virginia was a super-secret facility built by the US Navy.

Toward the end of the war, she worked in the drafting department. After the war, she worked at Sylvania and other factories that converted back to civilian production. In her twenties, she got a hearing aid and a cochlear implant in 2010

Bertha Glavin

Bertha was born in 1926 in Dorchester, MA (a section of Boston), and had four brothers and one sister. She started kindergarten in 1930 and graduated from the 8th grade in 1939, which was the 300th anniversary of the school, which was the first tax-supported school in the Country. Several months before she graduated from high school in 1943, the school gave her an address and told her to go there to work.

The factory made raincoats for the U.S. Navy, and she was to make out the payroll for the stitchers, who did piece work, which meant they were paid for each piece they sewed. She collected tickets from their baskets, gave them credit for each piece they had finished, and added 5% to their paycheck under the instruction of the Navy.

She married Martin Glavin, a Navy veteran in 1949, and they raised seven children, all of whom attended her historic school. She became president of the Home and School Association, was the school monitor for 22 years, and retired in 1992. In the meantime, she was vice president of the Dorchester Historical Society (Martin was president) and volunteered in the Quincy Library for several years.

Incidentally, her daughter, Martha, is an art teacher at her old school.

She was at the embassy when Rosies were honored there, and she has done a great job ringing bells for Rosies at the President’s Church on several Labor Days. She says, “I just keep hoping that I can do a good job for us Rosies.”

Neva Rees

Neva grew up on a dairy farm near Fairmont. She was one of twelve children, 6’2’ tall, and captain of her basketball team. After graduation from Fairmont High School, she went to Akron, Ohio where she built the control room for Goodyear Blimps, which were important in the war effort for surveillance and to direct ships and troops in silence. She still has some of her tools, which she bought to work at Goodyear, and she painted purple to recognize them easily on the workplace, which was often on scaffolds.

Her fiancé was sent to the Pacific, where he was in significant danger in the jungles of Guam. After the war, she nurtured him, and he had a premature death from malaria and other diseases he contracted from the war.

She had two sons, one died as a young adult, and one lives near her now in Marietta, Ohio.

Neva is known for her intelligence, her depth, and her lemon cookies. She is a writer, often telling about what life was like during the depression when she was a child and the family lost their farm.

(“Edie”) Johnson Lyons

Edie was born in 1918 in Fayette, County West Virginia. Her father discouraged her desire to be an artist, and now she is a leading Rosie artist. During World War II, she worked in many places from a shipyard in Virginia, to Nashville, Tennessee where she kept records of the performance of young men in pilot training, to Charleston, West Virginia where she was a secretary, often typing 12 carbon copies at a time, so If he made mistakes, she had to correct it on all the copies.

♪ ROSIE'S SONG ♪

American Rosie Movement™ commissioned Clinton Collins to write this song for our documentary film,

"We Pull Together: Rosie the Riveters, Then and Now", which we released in June, 2011.

Clinton is a gifted musician who wrote this song and sent it to us within hours of our request.

Thanks, Clinton, for a great job. You have helped us give a message that will live on.

THE DOL INDUCTS ROSIES INTO ITS HALL OF HONOR

The US Department of Labor included Rosie the Riveters in their Hall of Fame in September 2020. June Robbins, one of our board members, spoke for all Rosies at the induction.

Please see: http://bit.ly/Rosie-Hall-of-Honor_2020

To learn more about the Women’s Bureau and its celebration, please visit: www.dol.gov/wb

Buddie Curnutte holding the poster and letter sent to Rosies by the U.S. Department of Labor to advise Rosies that they had been inducted into the United States Department of Labor Hall of Honor. Buddie has helped to lay the foundation for the American Rosie Movement™, and, at 96, she says that being involved in creating projects and educating Americans about Rosies is one of the highlights of her life.